Tayu; ghosts of the past, beautiful actresses, or mysterious dancers? I need to admit that I had no clue about any details of the tayu profession when I arrived at the Yoshino Tayu Memorial back in April 2019. I’m still a bit puzzled, as the history records seem to be incomplete, so my tayu research is ongoing. Who are these alluring entertainers?

My first close contact with the tayu culture happened at the Josho temple (常照寺) in Kyoto. A friend invited me for a tea ceremony held there in the memory of Yoshino Tayu. This memorial is popular among the Kita-ku locals and history enthusiasts, but the majority of Kyoto inhabitants, as well as the visiting tourists, have no idea about such event. “I’m very happy that I can see a foreign face here today”—the priest hosting the Buddhist ceremony said suddenly during his speech and everyone started looking at me, smiling genuinely. This memorial is a hidden gem, shining extremely bright in the crown of Kyoto culture. I didn’t expect it to be so educative and mesmerizing.

Unfortunately, it was raining that day so tayu arrived in a rush at Josho-ji. Normally, they would walk very slowly, forming a procession called tayu dochu (太夫道中). During this famous parade, tayu wear 20-cm high black lacquered wooden clogs with three teeth (koma geta) and take sliding 8-shaped steps. They are accompanied by male servants who shade them with huge paper umbrellas and female attendants who play the role of personal assistants of tayu (hikifune 引舟). Tayu often put their palms on the servants’ arms or hold their hands to keep their balance.

The steps, which are performed in a shape of 8 (called hachimonji 八文字), require to place the koma geta inward. That’s why, sometimes, this particular movement of tayu is written as uchihachimonji 内八文字 to distinguish tayu from oiran (courtesans of Yoshiwara, Tokyo) who move their feet outward (sotohachimonji 外八文字) in an exaggerated manner. It’s a very important differentiation. Tayu are not the courtesans known from the famous ukiyo-e paintings of old Edo. Despite a similar appearance and mutual roots, tayu are considered to be the highest form of entertainment, derived from the Imperial court of Kyoto. Unlike oiran, who weren’t necessarily skillful in any form of art.

Before the II World War, a beautiful tayu dochu was held in Shimabara on the 21st day every month, with over a dozen of tayu showing off their elaborate dress. What is even more fascinating, each tayu used to form a small parade every time they were moving from one place to another. But nowadays, it’s extremely rare to see a tayu procession. It happens only for the special events and to celebrate the debut of a new tayu. The parades in the old times were accompanied by the fancy-dressed Shimabara geiko, who rode a cart decorated with artificial flowers (花車 hanaguruma) as they were holding folding fans in their hands.

Geiko and tayu co-existed in Shimabara for ages. Their role in the entertainment community was slightly different than tayu’s. It’s said that geiko provide entertainment for the common townspeople, while tayu are available only for the wealthiest customers—the Imperial court and daimyo, the feudal lords. It was (and still is) much more expensive to hire a tayu than a geiko. What is more, to meet a tayu, one had to go through complicated ceremonies testing their knowledge of court etiquette, dialect, and customs.

In the past, the most successful tayu had two kamuro (禿, child trainees), but some of the artists were presumptuous enough to keep six or even eight of the apprentices. The first tayu who paraded with two kamuro, breaking the rules of having only one apprentice, told the local council that she just borrowed the other girl and she’s not hers. Then, many tayu followed her example and started hiring more kamuro to elevate their position in tayu dochu and enhance their power in Shimabara. In Meiji and Taisho eras, the top tayu of Shimabara walked with up to eight kamuro and performed a special act during the parade, called kasa tome (傘止) or shingari (殿). Only once per procession, the best tayu with a few kamuro were able to stop the march to draw the crowd’s attention and make everyone marvel at their incredible costumes. Even though it was allowed to stop dochu only once, some of the willful tayu would perform kasa tome even twice or thrice.

Kamuro were very young girls up to 12-13 years old (they later become shome 少女 and, ultimately, tayu) running errands for tayu whom they belonged to. During the tayu dochu, kamuro sport the white oshiroi makeup, square-shaped bangs, and red costumes with their master’s name embroidered on the back. Kamuro were usually recruited from poor families around Kyoto city and its rural areas, but it was not the rule. They lived and worked at the pleasure district of Shimabara. Right now, kamuro are just the local girls who want to study the traditional arts, especially the dance. They live with their parents and go to regular school, join the art training at Shimabara in their free time. They may, but they don’t necessarily have to, become tayu in the future. It seems that it takes around 10 years to become a modern tayu from scratch, so much longer than to become a geiko.

Nowadays, Shimabara is almost extinct, as Gion and other geiko districts in Kyoto ruled it out. There’s only one tayu okiya left, called Wachigaiya, established around 1688 and operating even today. Officially, all legitimate modern tayu of Kyoto belong to Wachigaiya. There’s also an ageya-turned-museum, Sumiya (in business since 1641). Both of them have beautiful wooden facades of a typical Kyoto machiya. Sumiya seems to be the largest example in Kyoto of such style. Both buildings have alluring inner gardens facing the largest rooms, so the guests are able to admire the beauty of Japanese horticulture while enjoying a party. Typically, a tea ceremony room was installed in the garden, so every ageya could hold tea ceremonies, as well.

Ageya (揚屋; age 揚 – to raise, elevate, ya 屋 – establishment) is a place where banquets with tayu are held. It’s called ageya because the parties were organized on the second floor usually, so the guests were being “elevated” from the first floor. Only the noblest patrons may access ageya. Unlike ochaya, ageya had their own kitchens (on the first floor) and the meals were prepared on the spot. Ageya is like a club or salon, where wealthy men spent long hours being entertained, drinking, and dining. When a tayu was called to an ageya, she would walk there forming the procession mentioned above (tayu dochu) with all of her entourage. The most famous tayu used to compete in having the most ostentatious retinue (i.e. the number of kamuro) and it resulted in official limitations later on.

Ageya existed until the Meiji period and then most of them got incorporated into ochaya (teahouses), as they were quite similar. Similar to Gion, tayu and geiko were sent to the ageya/ochaya and lived at okiya, but around Meiji, some ochaya/ageya blended with okiya—it became a standard for a renowned okiya to have an ochaya, as well. Hence Wachigaiya in Shimabara is both an okiya and an ochaya. Other ochaya/ageya transformed into ryotei, a traditional Japanese restaurant mixed with a cultural salon.

Shimabara (official name: 西新屋敷 Nishishinyashiki) was not only the tayu district but a geiko and maiko dwelling as well, until the 1970s. The joint hanamachi union in Kyoto included Shimabara. Shimabara geiko had their own stage performances (i.e. Aoyagi Odori 青柳踊), just like Miyako Odori in Gion Kobu or Kitano Odori in Kamishichiken. But the truth is, in the Meiji period, Gion has already become the main entertainment center of Kyoto rather than Shimabara, mostly due to the latter’s inconvenient location (similar case in 2020: Kamishichiken). Nowadays, Shimabara is a tranquil area with some ordinary houses, a few machiya, and the characteristic gate that can be found in old photographs. Shimabara was originally surrounded by a moat and stone walls since the entertainment districts used to be built as separate towns to keep the local people away from temptations. But Shimabara wasn’t completely secluded, unlike Edo’s Yoshiwara—the gate was always open (from 1842) for entering and even tayu were able to move back and forth more or less freely.

Shimabara had every form of entertainment (bars, teahouses, eateries, musicians, theatre troupes, comedians, dancers…), it wasn’t limited to being a red-light district. An ochaya is something we could call “a club” or “association” nowadays, where loyal customers gather to meet with and admire their favorite artists, and Shimabara (just like Gion and others) relied on ochaya/ageya. But the shogunate aimed to prevent people from being too amused and relaxed, hence these districts, such as Shimabara, became licensed and controlled zones. Shimabara was originally located a little bit closer to the center of Kyoto and called Yanagicho Nijo (around the Nijo street), later moved to the Rokujo street area and got a name of Rokujo Sansuji (六条三筋) to eventually become Shimabara, a town built in the middle of cultivated rice fields. Shimabara holds a proud title of the oldest kagai in Japan, with 600 years of history, starting in the Muromachi period. Shimabara, in contrast with Yoshiwara known from ukiyo-e, has strong connections with the traditional art. Many art genres originated there—for example, haiku poetry was invented in Shimabara. There also was a kaburenjo theatre for performing arts established in 1868, but unfortunately, it got torn down in 1996. Back then, there were around 50 okiya and 20 ageya taking care of the local artists. Shimabara ceased its activity as an official kagai in 1977 due to the lack of demand for its services.

But who exactly are tayu, the enigmatic entertainers of Shimabara? The definition and history of tayu are quite hazy and difficult to understand. Tayu’s culture is one of the most spectacular aspects of the Japanese national heritage, but their story is usually omitted, hidden, or simply misinterpreted. What we know for a fact, tayu were the highest-ranked entertainers in the pleasure districts of the old Kyoto, but it doesn’t mean they were selling their bodies, as the lower-ranked courtesans were obliged to. According to Sumiya, “tayu are in a sense the highest rank entertainers in the geisha category”. Tayu represent the romantic idea of love and physical satisfaction was not the main goal of meeting them, thus they are considered as artists and entertainers, not courtesans. Tayu were much more than just the paid company; they were rather high-quality artists trained since childhood by the finest masters of poetry, dance, flower arrangement, music, conversation and etiquette, the way of tea, court games, and calligraphy. They’ve developed a peculiar appearance, compliant with and even beyond the beauty and fashion standards of the Imperial Court (at some point, tayu became the trendsetters and symbols of an ultimate Japanese beauty). In this case, they were precursors of modern geiko and maiko, but much more tied with the Imperial traditions. Some tayu might have become ones of the most powerful women in Japanese society in the time of their biggest popularity.

Being a tayu was not the simplest path. Massive competition, zero independence (tayu were completely dependable on their okiya, as the okiya created their brand), intensive art practice, questionable work safety (some tayu were victims of several fires in Shimabara). Only the most enduring women could achieve the title of tayu. But tayu had unusual freedom in choosing the customers, appointment dates, and controlling the meetings’ scenarios. Moreover, they were able to meet the Emperor and that has been the biggest privilege in Japan.

The hierarchy ladder was rather complex and quite unclear for us nowadays. There were several types of women working and living in Shimabara (detached from the rest of the city), including:

- Tayu, serving the noble customers exclusively for an extremely high price and requiring deep knowledge of etiquette, customs, and court dialect. The highest rank of tayu was keisei (傾城).

- Sanha 三八, rank between tayu and tenjin.

- Tenjin 天神, tayu apprentice. They were called tenjin because they cost a fee of 25 for their company and the famous Tenjin market is held at Kitano Tenmangu on the 25th day each month.

- Hikifune 引舟 – tayu’s personal assistant, usually retired tenjin.

- Kamuro 禿 – children in training, later promoted to shome.

There are no ranks other than tayu, furisode tayu (like a minarai in the geiko districts), shome, and kamuro nowadays. Tayu are traditionally associated with pine in the Japanese art and tenjin were symbolized by plum (ume) blossoms.

Tayu have been the highest and finest form of entertainment, reserved only for the wealthiest and most important people in Japan. Entertaining the imperial family has remained their main job for ages. Especially now, they’re even more elusive than ever. Only 5 tayu are left in the whole country and the art they practice is truly mesmerizing. It’s almost impossible for an ordinary person to witness the art of tayu. They hide from the public eye and focus on secrecy and mystery. They’re almost like some form of a legendary unit for special purposes!

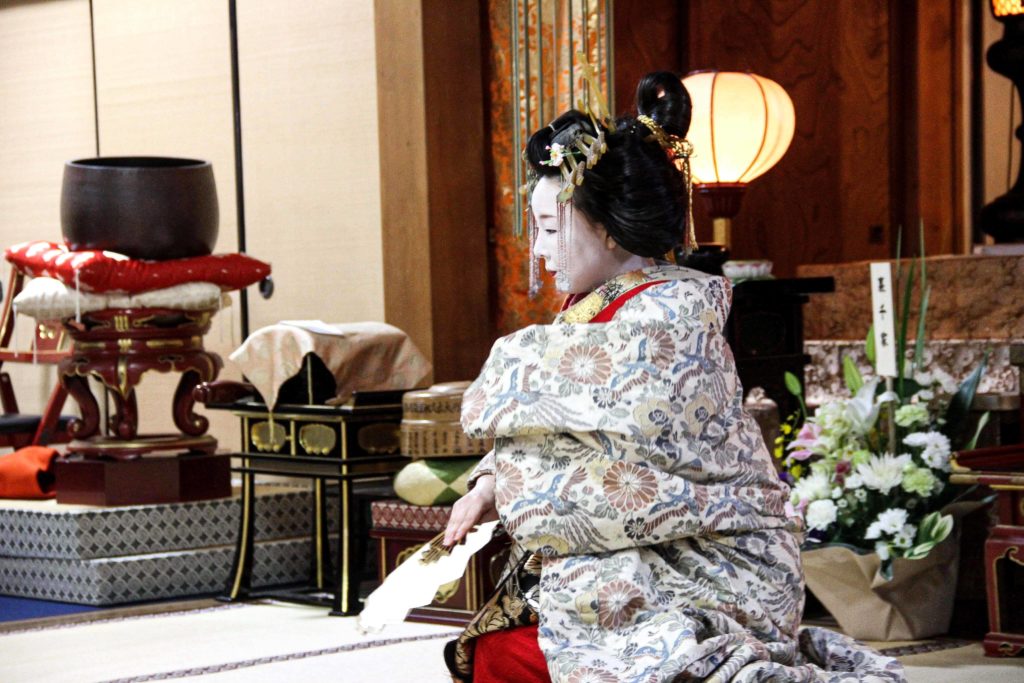

Tayu’s appearance is so rich and vivid, it’s hard to believe they’re real women, not sculptures or dolls from the Edo period. Tayu style their own hair and decorate it with fluttering silver kanzashi, hanakanzashi (silk flowers, similar to maiko), bead strings, and tortoise-shell pins, everything combined weighing 3-4 kilograms. When I saw a tayu for the first time, I couldn’t help but think that geiko and maiko look… quite humble. It’s true—geiko and maiko ruled out tayu because of their simplicity. Tayu represent a different epitome of elegance and grace which just went out of fashion at some point due to the social, economic, and political changes in old Japan. I dare to write that many cultures around the world faced similar changes. Geiko became more accessible, easier to approach and understand by the commoners. Tayu nurtured the traditions and etiquette from the Imperial Court, deep spirituality, complicated rituals, heavy Kyoto dialect, social hierarchy, and high wealth. It stays this way even today. Close contact with tayu is truly an out-of-this-world experience.

Tayu use the oshiroi type of makeup, fashionable at the Imperial Court back in the Heian period. They also use ohaguro—teeth blackening (maybe you remember this practice from maiko’s sakkou stage). Back in the Heian period, it was disgraceful to show bare teeth at the Imperial court. Teeth blackening gained popularity among married women in the Edo period later. It was a part of coming-of-age and transition between childhood and married, mature life. Tayu adopted this custom to enhance their symbolic marriage with art. Correspondingly, tayu shave their eyebrows (a habit called hikimayu 引眉). Ohaguro and hikimayu were done to quickly distinguish wives from unmarried girls, in the case of common people. Both of these procedures used to be performed for beauty purposes and it seems that Japan wasn’t the only one place with teeth blackening. Such practice was found in Cambodia, South America, Borneo, and Russia.

Tayu paint red the lower lip only. If you compare it with geiko and maiko’s makeup, you can notice that only the first-year maiko keep their upper lips uncolored. But back in the days (even shortly before the II World War), it was a beauty standard to highlight only the lower lip, so geiko and maiko followed suit. Painting both lips seems like a modern addition to the geisha’s code.

The whole kimono outfit of a tayu weighs around 30 kilograms. The same kind of kimono is worn even in the peak of summer and in the terrible heat (but we have to keep in mind that recently we’re experiencing the highest temperatures in the history). The kimono I saw at Josho-ji are antique, dated back to the Taisho and Meiji periods. One obi and kimono is worth 6000 000 yen, according to tayu Kisaragi. Tayu’s kimono is a simplified version of the court’s junihitoe (12-layer kimono from the Heian period). An important detail is a twisted collar, showing a scarlet inner fabric. This particular shade is a symbol of noble rank and it functions like a passport to the Imperial Palace. Geiko use this kind of collar for a tea ceremony before the odori performances. Why? It might be because, before the II World War, tayu used to host the odori tea ceremony in Gion.

Tayu wear their obi in the front and the most popular misconception says that it’s worn this way to be easily untied. Quite the contrary—this tie is very difficult to get undone. So why they put it in the front instead of the back? Simply, to show off the wealth. Such obi are extremely expensive and while tayu wear a richly embroidered coat (uchikake) on their backs, obi would remain unnoticeable. What is more, it was fashionable for the noble wives to wear their obi in the front because it meant that they had servants at home (obi in the front makes it difficult to do the house chores). Obi tied in the back gained fame among the Edo townspeople. It was easier to run errands with your obi in the back, not front. The commoners were a target for geisha, thus they also wear their obi in the back to appear more approachable and easier to talk to than the tayu.

Tayu’s obi is arranged in the shape of a heart and called manaita (心形 ) or Shimabara musubi, written with a kanji for heart 心. As it’s a very powerful symbol that represents Kyoto’s omotenashi (hospitality, gentleness, elegance), tayu put their hands underneath the obi to respect this sign and not to hide their heart and true intentions. This humbleness is also expressed in staying barefoot all year long—bare feet mean that even though tayu are of noble rank, they’re always one step behind the customer who’s the most important figure at the zashiki.

The April memorial at Josho-ji is dedicated to the legendary Yoshino tayu from Shimabara. This hanamachi produced a lot of famous entertainers, but five of them were truly unforgettable—Yoshino (吉野), Yugiri (夕霧), Yachiyo (八千代), Ohashi (大橋), and Sakuragi (桜木). These women were so renowned, that their names are carried over to the further generations of tayu. That’s why there’s a Sakuragi tayu in 2020, as well. Carrying a famous name (名跡 myoseki) requires the tayu to represent it properly. In general, tayu’s names originated from “The Tale of Genji” (such names are called genjina 源氏名), but of course, some tayu got their names after beautiful places in Japan or elegant metaphors.

Yoshino tayu was born in 1606 “close to the Great Buddha of Kyoto” (Houkou-ji 方広寺 in Higashiyama; near the National Museum in Kyoto) as Tokuko (?) Matsuda (松田徳子). Her father, Buemon Matsuda (松田武右衛門), was a samurai. At the age of 7, Tokuko was sold to the okiya Rinyojiro (林与次郎) in Rokusansuji (the whole district transformed into Shimabara later). She became a kamuro there under Hizen tayu (肥前太夫) and was renamed Rinya (林弥 or 林彌, depending on the source). Rinya was extraordinarily beautiful and got promoted to tayu at the age of 14. At first, her tayu name was Ukifune (浮舟), but it was quickly changed to Yoshino when the Rinyojiro owners realized that she’s incredibly skillful in art. She was the second tayu in the history of Shimabara to bear the name of Yoshino. It’s said that Yoshino was exceptionally smart and many poems composed by her proves this fact. Except poetry, Yoshino practiced literature, koto, Japanese lute (biwa), Japanese reed instrument (sho 笙), tea ceremony, incense ceremony, flower arrangement, kaiawase (shell-matching game of the Heian period), and Go game.

There are many stories involving Yoshino. Once, on a sunny day, there was a huge party with 18 tayu who dressed their best costumes. But Yoshino tayu was absent. It seems she stayed up with a customer until morning. When a servant called for her, she appeared with her hair messed up in sleep, wearing only white underwear and a black coat tied with a purple sash, but even in such attire, she was more stunning than the rest of the tayu. Another anecdote says that one disciple of a swordsmith was a great fan of Yoshino. He worked super hard to gather the money to meet with her but was denied. Hearing that, Yoshino felt sorry for him and invited him to spend a night with her. Afterward, the apprentice jumped into the Katsura river, yelling: “Now I have nothing more to remember in this world”.

今は世に思い残すことなし—

Nothing more to remember in this world

Yoshino tayu got deeply associated with the Josho temple when one night a dirty-looking monk came to the ageya in Rokusansuji and asked to show him Yoshino. He was refused but keep on insisting. Yoshino heard the fight and decided to reveal herself. Seeing her, the Buddhist priest put the 100 sen he borrowed from the believers on the counter and left. Yoshino thought it was strange and followed him. It turned out that he was the high priest of Josho-ji and Yoshino became devoted to this temple since that night.

At the age of 26, Yoshino was freed from Shimabara by Shoeki Haiya, a wealthy merchant and a culture patron. They got married but Yoshino died unexpectedly on August 25, 1643. She was only 38 years old. Shoeki was devastated. After saying a prayer, he mixed her ashes altogether with sake and drank it down. Yoshino’s grave was installed at Josho-ji and since then, every April, the Shimabara tayu gather there to pray and perform a tea ceremony in the memory of the most beautiful and talented tayu in the Japanese history.

都をば花なき里になしにけり 吉野は死での山にうつして—

Kyoto became a flowerless city, as Yoshino moved to the land of death

To complete the reading, let’s enjoy the tea ceremony performed by Wakagumo tayu. As a tea ceremony is always enjoyed in silence, I’m not attaching any text to these pictures. Please study the photos and the particular movements performed by tayu Wakagumo carefully, and feel like a guest of a tea ceremony in old Shimabara.

才智深く心情篤く、容顔艶麗にして花を欺き、一度口を開けば心融けざる者なく、一度見えて迷わざるなし

She was witty and extremely beautiful, but with a kind heart. Her stunning features could be compared to a flower. she melted hearts with every word she said. One glimpse at her and your worries are gone.一an excerpt about yoshino tayu

Fact source: Yoshino Tayu memorial, Zomeki san’s blog

Photos: © 2019 Geishakai

Subscribe to my Patreon and gain access to the exclusive videos from the Yoshino Tayu memorial

Świetny artykuł i rewelacyjne zdjęcia! Pozdrawiam serdecznie!

Dziękuję bardzo! Cieszę się niezmiernie, że Ci się podoba! 🙂

Wow!! Great reading Mari!!

So much information!!

Thank you! I tried my best!

Thank you for this wonderful post! It must have taken a long time to get all that information! Wonderful pictures only made this post even better!

Keep safe!

Thank you so much for your kind comment!

Yes, it took me one year to finally write about my encounter with these amazing artists and 4 weeks to refresh my knowledge and complete the additional research in Japanese… but it was worth it. I’m glad you like it! 🙂

Stay healthy!

Really appreciate your research. Reliable information about Tayu has been so difficult to find so your grounded work is very helpful. It’s good when you also say what is unclear as well. Thanks so very much.

I’m always happy to receive a positive feedback from you. Thank you so much!

Still a lot to study though…

Great writing and valuable information. Thank you!

[…] Read my previous article about tayu of Shimabara. […]