The iconic and fascinating look of Kyoto maiko has probably made you want to try it on even once. You can make this dream come true in Kyoto—just visit one of the many makeover studios! You can become a maiko for a couple of hours there, experience the white makeup and heavy kimono outfit, and take great souvenir photos. But which maiko makeover studio is the most reliable? Is it expensive? How does the process look like? Let’s transform into a maiko with me!

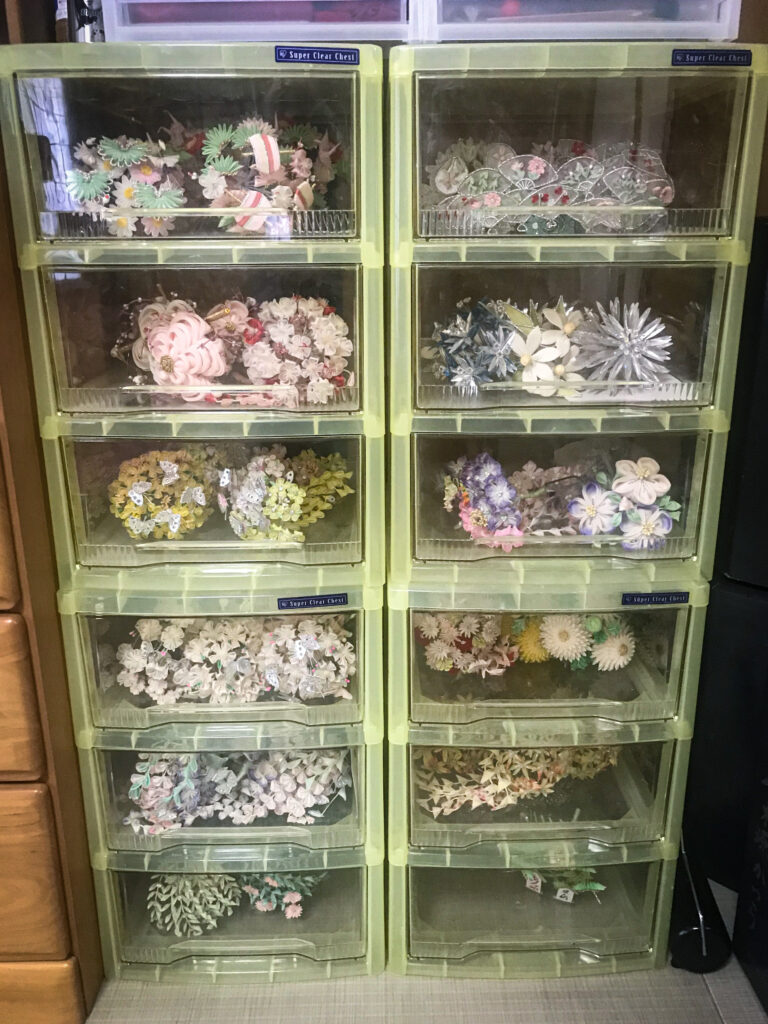

Quality is the most important for me and, unfortunately, Kyoto has got a lot of services that can be labeled as a “tourist trap”. There are too many inaccurate makeover studios that offer ridiculous-looking dress-ups. Some speculate that such poor-quality maiko makeovers are done on purpose, so they would not be mistaken with the real deal on the historical streets of Gion. But, in reality, it’s just cheaper and easier to dress up tourists, who don’t know better, in a somewhat maiko-resembling random kimono fashion. I decided to turn to the best source of maiko’s accessories, a real okiya (maiko lodging house) run in Kamishichiken by a former geiko named Katsufumi. It seems to be the only one remaining henshin studio run by the okiya/otokoshi. The rest of these shut down recently, unfortunately.

Katsufumi retired many years ago but she inherited a teahouse located on the main alley of Kamishichiken. It has been operating as an ochaya, bar, and a makeover studio since. Thankfully for the tiny Kamishichiken hanamachi, in 2017 Katsufumi decided to establish an okiya too, with its very first maiko Fumiyuki (now a senior maiko). While the okiya, ochaya, and bar can be accessed upon an invitation only, the henshin studio on the first floor is open for everyone upon a booking.

The studio is the most accurate one, as Katsufumi looks after every single detail of the makeover by herself. Being transformed into a maiko by a real okiya proprietress is really a magnificent and unique opportunity. That being said, some strict rules are in power as well. While I was able to choose my favorite kanzashi, I had to comply with the accurate kimono array, makeup pattern, and the hairstyle shape. I intentionally booked an appointment at Katsufumi’s in May, as I’ve always been in love with the weeping wisteria kanzashi in pastel colors. And I wanted to understand maiko more, so I decided to give it a try.

To my surprise, I was able to choose the kimono I like, as well (maiko are not allowed to do so, every coordination is chosen for them by the okiya owner). There were several kimono suitable for May in the catalog offered by the okasan, and I instantly fell in love with a beautiful cream-and-blue hikizuri with handpainted insect cages. It seems that maiko Fumiyuki also likes this particular kimono.

While I’m used to wearing a kimono, I was shocked about the weight of the collar sewn onto a juban (underwear). The collar is made of heavy embroidery, so no wonder why it weighs so much, but it’s hard to imagine wearing such a collar in summer! Maiko have no choice, however. The same collar is worn all year long. It made me admire their dedication even more.

Katsufumi san started painting my face as soon as I changed into a light yukata. First, she carefully tied up my hair and pressed the wax base into my skin. More about the oshiroi makeup process HERE.

The white paste is really light-weight. I expected it to be a bit thicker, but I couldn’t feel it on my skin at all. Unlike some heavy foundations of the popular drugstore brands… Oshiroi is sold as a white or pink loose powder, then mixed with water before applying. Water quality is crucial. Tap water is usually too harsh for the cosmetic, so it’s better to use spring water.

Even though the makeup has strict rules to follow, every artist has their own style and creates a different, unique face. Mrs. Katsufumi drew her own maiko-era face on mine. If I was doing the makeup by myself, I’d probably paint something different. Every time I watch an artist applying oshiroi, I find major differences in the application style, shape, color choice, etc. Sometimes the pink base goes upwards, other times it’s applied underneath the white layer. The contoured areas also wary, depending on the bone structure of the artist. Some of the maiko use the “Western” makeup techniques, too. My makeup that day was very proper and Japanese to make it look the most authentic as possible.

All Kyoto maiko style their real hair in complicated nihongami. Obviously, Katsufumi san is not a hairstylist, so we decided to use a very handy half-wig placed only on the back of the head. It worked like a frame of the wareshinobu hairstyle. My own hair was spread evenly over the base and Mrs. Katsufumi blended it into the wig. She used a temporary coloring spray to turn my hair black for a couple of hours. The half-wig was quite heavy but it created an authentic, natural look.

Then, finally, I could put on the lovely clover-and-insect-cages kimono I chose earlier. It wasn’t heavy at all, I could feel the collar’s (sewn into the juban) weight only. Mrs. Katsufumi dressed me up professionally. The kimono worn by maiko and geiko with the white makeup is quite different than the normal kimono worn by ordinary women. It’s a hikizuri (or susohiki) type, much longer (up to 200 cm or even more), trailing on the floor (I always picture it in my mind as a mermaid tail). Hikizuri is used on stage by dancers of nihonbuyo. Maiko and geiko entertain their customers several times per day with their dancing skills, so naturally, they wear this kind of kimono each time they go to work.

Due to its big size, hikizuri can be worn by every body type. It’s easily fitted by adjusting the amount of fabric tucked and hidden behind the obi. Dancers of nihonbuyo don’t need to worry about their measurements or height, hikizuri fits everyone. I have a massive issue with my long arms, as the standard kimono’s sleeves are usually too short for me, but hikizuri seems to be perfect. It’s a wonderful kimono!

In districts like Gion Kobu or Miyagawacho, a male dresser (otokoshi) visits geiko and maiko every day to help them with kitsuke. It makes sense time-wise, as these hanamachi are huge and there’s a large number of women to be dressed up at once. But in smaller districts (i.e. Kamishichiken or Pontocho) maiko and geiko rely on the okiya sisterhood. The most difficult part of the hikizuri kitsuke is darari obi. It takes a lot of physical strength to tie it (hence the male helpers in bigger districts). At Katsufumi’s we used an “easy” darari obi cut in half so it wasn’t too difficult for the female staff to tie it.

Maiko and geiko of Kyoto wear pure silk kimono handpainted in the Kyo-yuzen manner by local artists. Originally, all okiya supplied at the Nishijin district (located close to Kamishichiken), famous for its Kyo-yuzen craftsmanship. This technique applies dye directly into the fabric with the aid of a special glue. This way, the painting looks like a pattern and doesn’t stain. Kyo-yuzen kimono have a very traditional appearance.

The final effect:

Note: out of respect for the local geiko and maiko community, the Katsufumi studio doesn’t let you walk outside in the maiko/geiko outfit. There’s a studio photoshoot and photo prints included in the price.

Photographs: geishakai, Paul van der Veer