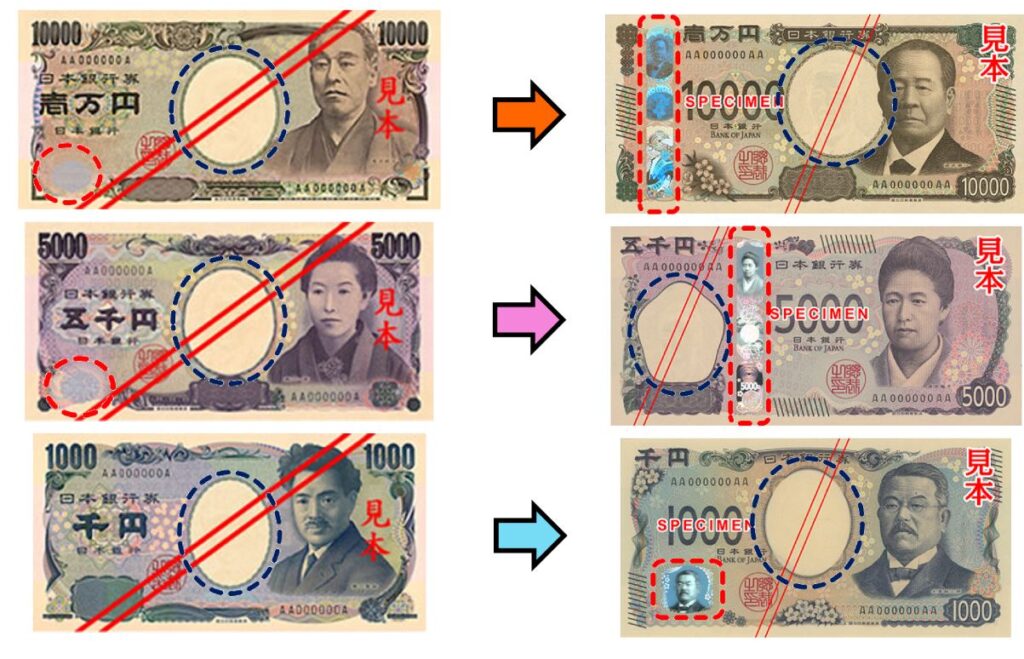

The Japanese government recently unveiled new banknotes. They reflect Japan’s artistic traditions and embody the nation’s dedication to innovation and progress. The 5,000 yen banknote is especially remarkable as it features a woman whose impact transcends her time and leaves an enduring legacy. Her name is Tsuda Umeko, a Japanese educator and women’s rights advocate.

The new banknotes (set to be introduced in the first half of July 2024) pay homage to Japan’s cultural heritage, with each denomination featuring iconic elements that hold significant historical and cultural importance. For instance, the ¥1,000 banknote showcases the renowned Hokusai’s woodblock print, “The Great Wave off Kanagawa”. It is undoubtedly a worldwide symbol of Japanese art, recognized by most people. Meanwhile, the ¥5,000 banknote is purple and highlights wisteria flowers, a consistent part of Japanese flora in art. Lastly, the ¥10,000 banknote prominently portrays the well-known red-brick building of Tokyo’s Marunouchi station, an Important Cultural Property of Japan.

While two of the banknotes feature men (Shibasaburo Kitasato, a microbiologist, on the ¥1,000 note, and Eiichi Shibusawa, a business leader, on the ¥10,000 banknote), ¥5,000 one has a kind-looking woman in kimono. She is smiling faintly and sporting a simple Gibson Girl hairstyle (yohatsu 洋髪, as it was called in Taisho-era Japan). A contrasting image to her precedent, the current ¥5,000 face, stern-looking Ichiyo Higuchi. The new ¥5,000 model is Umeko Tsuda, a historical figure especially close to my heart.

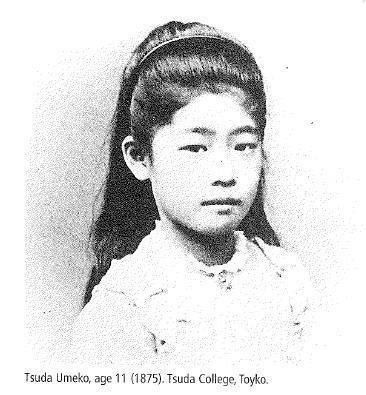

Born in 1864’s Tokyo, during a period of significant social and political change in Japan, Umeko’s life journey and contributions have shaped the landscape of women’s education and empowerment in her country and beyond. Her original name, Ume 梅 (lit. plum blossom), was changed to Umeko 梅子, as it was considered less old-fashioned. Indeed, XX-century Japan saw a real boom of girls’ names ending with -ko (-子). Such names, seen as cute and feminine back then, are nowadays decreasing in popularity. Modern parents are more likely to choose “an old-fashioned” name instead.

Ume was the daughter of Sen Tsuda, a politician, educator, and the founder of Aoyama Gakuin University. Sen, a low-ranked samurai from Chiba and a West enthusiast, had a revolutionary vision of women’s education. Girls of the Meiji period had practically almost no chance to attend a university. Wealthy families could afford to send their daughters to primary school where they learned how to read and write, but even these elite girls were sacrificed to be housewives as soon as they were ready to marry – usually in their teenage years. The common school did not offer valuable courses for girls either. Their curriculum was different than the subjects for boys – cooking and etiquette classes were forced upon girls, while male students could freely excel in physics, chemistry, or biology.

Countryside girls from poor and disadvantaged families suffered a much more miserable fate. Without any opportunity to get a proper education, with their parents usually too poor to even feed and sustain their daughters, it was not rare to sell them in early childhood as servants to the red-light districts. A girl’s life was not of a high value. With a bit of luck she could become a geisha. With more luck and determination, she could even marry a customer or gain a rich patron and lead a slightly more comfortable life. With less luck though…

Ume’s father was a visioner with globalist values and a mission to improve the future of the following Japanese generation. Along with his wife, Hatsuko, a Westernization evangelist, he cooperated with foreigners in order to modernize Japan after years of isolation. Sen Tsuda was a prominent entrepreneur in the Meiji period, hence, he was well-informed of the most critical events in the country.

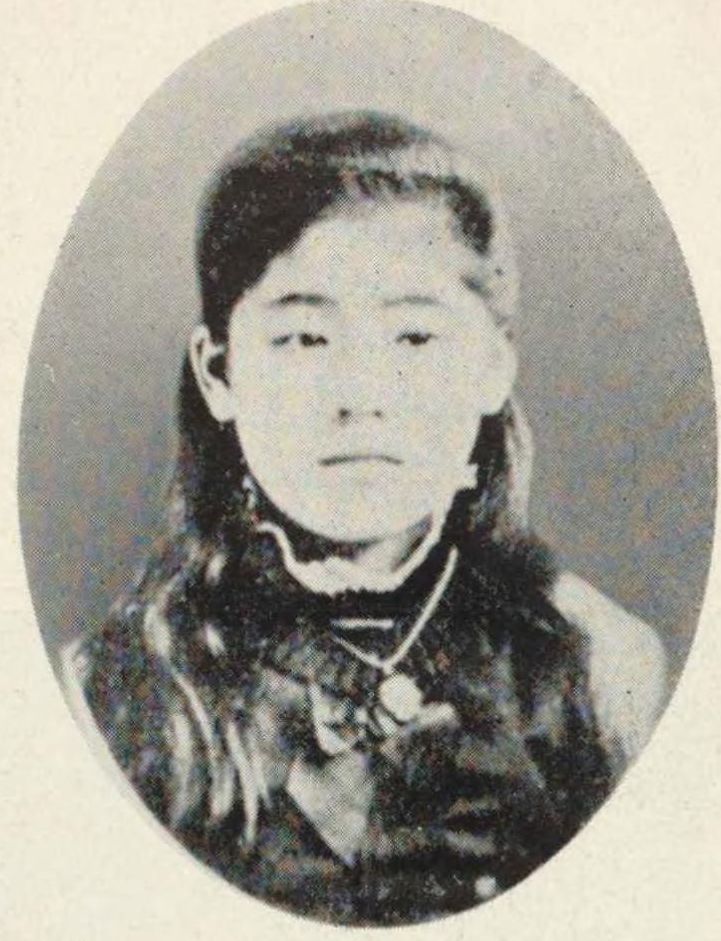

When Tomomi Iwakura formed his diplomatic mission in 1871, Tsuda immediately volunteered his beloved six-year-old Ume to be taken aboard on a ship to the United States. That was her once-in-a-lifetime chance to secure a better future. Incredibly risky mission, if we think about it nowadays. Yet, the Tsuda family was desperate to educate their daughter and break the chains of an inevitable housewife fate.

Thus, little Ume joined four teenage girls on the ship to San Francisco as the youngest member of Iwakura’s expedition. As it was a journey towards the unknown without the parents, there were no other applicants despite a generous stipend. Ume was entrusted to Charles Lanman’s home in Washington, D.C., where she was raised almost like an adopted child. She learned English while attending school in Georgetown and graduated with awards in writing and arithmetic. Ume blended into the American uptown girls’ society so much that she almost lost the ability to speak Japanese upon her return.

The diplomatic mission finished after two years, but Ume stayed in the US until she was 18. The agreement between Sen Tsuda and Lanman ended, and it was time to finally “go home”. Returning to patriarchal Japan was a shocking and painful experience for Ume. Suddenly, her freedom to form opinions and get further education was tragically limited. As a Japanese girl, she had to fulfill the image of ideal womanhood (yamato nadeshiko). Never question a man; always walk in the back. Even nowadays (2023), many Japanese companies require female employees to serve tea during meetings while the male workers debate. Japanese academia is also dominated by men.

Ume was hired by the prime minister, Hirobumi Ito, as a tutor for the politicians’ children, along with her American school friend, Alice Bacon. However, Ume’s anger and dissatisfaction with the position of women in Japanese society was growing. She was not allowed to teach anything useful to the nobility’s daughters, as their fathers required Ume to show the girls how to be obedient. Her students were, after all, predestined to give birth and cook for their husbands after graduating from school. No career in science or economics was available for them. A woman’s worth was merely judged on her fertility and ability to be submissive.

Disenchantment led to Ume’s return to the United States in 1889. She was able to obtain a college degree only abroad. It was yet to be available for girls in Japan, as the education path was closed after completing school. Ume wanted to prove her abilities by majoring in biology and researching frog eggs’ development. She recognized her privileged position – her studies would not be possible if she were raised in poverty. Therefore, she started lobbying for an equal education for all Japanese students. Her school, Women’s Institute for English Studies (now Tsuda University, one of the most prestigious colleges for women) in Tokyo, accepted girls from all social classes. Hence, the school suffered financial issues.

Despite this, Ume did not give up on her educational mission. She changed her name to Umeko to mark her independence. Changing names was a widespread custom in Japan upon every major turning point in life. Accordingly, a fellow female student from the Iwakura expedition was renamed by her mother before embarking on the ship from Yokohama. From Sakiko 咲子 (“Blooming Child”) to derogatory Sutematsu 捨松 (“a pine thrown away”). Sutematsu never changed her name again; she used it with pride, as studying in the USA completely changed her as a person. Girls from the Iwakura mission (and their parents) could face backlash in Japanese society, but they were called “Japanese princesses” in the American media.

Tsuda Umeko’s story reminds us that the fight for empowerment and equality is an ongoing journey that requires the collective efforts of society as a whole. Her vision and dedication to breaking down gender barriers have left an indelible mark on Japan’s history. From 2024, we can celebrate her legacy each time we pay with a ¥5,000 banknote.

If you like this article, buy me a ramen or join me on Patreon! I don’t run any ads on my website so your support is the only way to keep it active ♡

Thank you for this. I was excited, and surprised when it was announced a woman would appear on the next ¥5,000 note. It’s about time! Though there is still room for improvement for women everywhere, not just Japan, her life and legacy serve as a constant reminder of the value and importance if equality for women. It is a woman’s birthright.

Arcyciekawy artykuł! Dziękuję za przybliżenie postaci Umeko Tsuda!

Dziękuję za miły komentarz 🙂 proszę rozsyłać dalej <3