Nestled in the heart of Kyoto, Shimabara is a district steeped in history and cultural significance. This quaint neighborhood exudes an old-world charm that harks back to ancient times, offering visitors a chance to immerse themselves in the traditional essence of Japan. Its very last bastion, Sumiya, stands as a testament to the enduring allure of Shimabara’s legacy.

Read my previous article about tayu of Shimabara.

Kyoto, the cultural capital of Japan, is renowned for its magnificent temples, beautiful gardens, and captivating traditional arts. However, beneath the serene surface lies a fascinating aspect of the city’s history – the old red-light districts, known as 遊廓 yukaku. These districts, though often associated with entertainment and pleasure, played a significant role in shaping Kyoto’s social fabric and cultural identity.

The genesis of Kyoto’s red-light districts can be traced back to the flourishing Edo period, a time of peace and prosperity in Japan. As the city’s population grew, the demand for entertainment and artistic expression surged. To cater to these needs, designated districts were established, becoming hubs of art, culture, and refined social gatherings. Among these, also physical pleasures for the elite like eating, drinking, and lovemaking. Such enclosed towns were built at the outskirts of the cities, usually in the areas of unlucky or taboo connotations. Shimabara was not an exception, yet it was frequented by famous historical figures. Now a little bit forgotten, Shimabara used to be a cultural mecca, where artistic expression thrived.

The role and meaning of tayu is difficult to grasp from the modern and, most importantly, Western point of view. The closest modern equivalent to tayu would be a nationally famous female beauty guru excelling in dance and music, owned by a strict talent agency, whose main job is entertaining extremely wealthy and influential guests at banquets as a hostess. In other words, tayu were the celebrities of the Muromachi, Momoyama, and Edo periods in Kyoto. Their ranks varied as the guests’ status varied—tenjin-titled entertainers were consorts of elite samurai or clergy, while tayu became the Imperial concubines or companions for daimyo (feudal lords). As with every other profession back in the old times, being a tayu was more of a lifestyle than a contract job. Japanese society was free of the Christian values adopted later as a global standard. Hence, Shimabara was the land of hedonism and, later in the Bakumatsu and Meiji periods, decadence. It was a gateway to the world that I like to compare with the European Belle Époque of the XIX century. In addition, ageya were not brothels but the Japanese equivalents of European salons or cultural clubs from the aforementioned era. Kyoto’s Shimabara is often compared with Tokyo’s (Edo’s) Yoshiwara, the cursed and miserable district of condemnation. To be historically accurate, it is necessary to contrast these two towns, as Yoshiwara lacked any ageya and tayu and, for good reasons, is considered to be one of the darkest areas of old Edo. Yoshiwara’s bad fame successfully covered Shimabara’s glory with a shroud of shame and taboo, after the last geiko moved out from Shimabara in the XX century.

Walking through the narrow streets of Shimabara, visitors are greeted with a charming display of traditional Japanese architecture. The district is adorned with wooden machiya townhouses, many of which have been carefully preserved to retain their original grandeur. These well-preserved buildings add to Shimabara’s unique appeal and provide a glimpse into the architectural styles of the past. Among the notable landmarks is Sumiya, a revered ageya-turned-museum that encapsulates the elegance and grace of Kyoto’s cultural salon. It offers a fascinating tour into the world of tayu, presenting visitors with a deep experience that is both enlightening and enchanting.

Sumiya was constructed during the Edo period in the 17th century. Originally established as a prestigious teahouse for affluent merchants and samurai, the building eventually evolved into an exclusive venue for tayu entertainment and banquets. Throughout its history, Sumiya has been carefully preserved, with its traditional architecture and interior decor remaining remarkably intact. It has never been a living quarter and this fact might contribute to its pristine condition.

Other machiya in Kyoto have a narrow facade, as the tax for long buildings was relatively high. Sumiya’s long facade is a bold statement of its financial situation.

Shimabara’s Sumiyoshi shrine from 1732 (seen below in the middle)—the guardian deity of the neighbourhood. All tayu parades and festivals had a starting point here.

Stepping through the sliding doors of Sumiya, visitors are immediately struck by the architectural brilliance that defines the teahouse. The structure boasts a quintessential Edo-period design, characterized by its wooden lattice windows, elegant painted sliding doors, all based on surrounding Buddhist temples’ design. Every inch of Sumiya oozes charm, displaying the remarkable craftsmanship and attention to detail that exemplifies Japanese architecture. Sumiya is the only one ageya that survived to our days and it’s listed as the National Important Cultural Property. It was a unique place even in its contemporary times, as it was astonishing the guests with the largest banquet hall ever constructed in Kyoto.

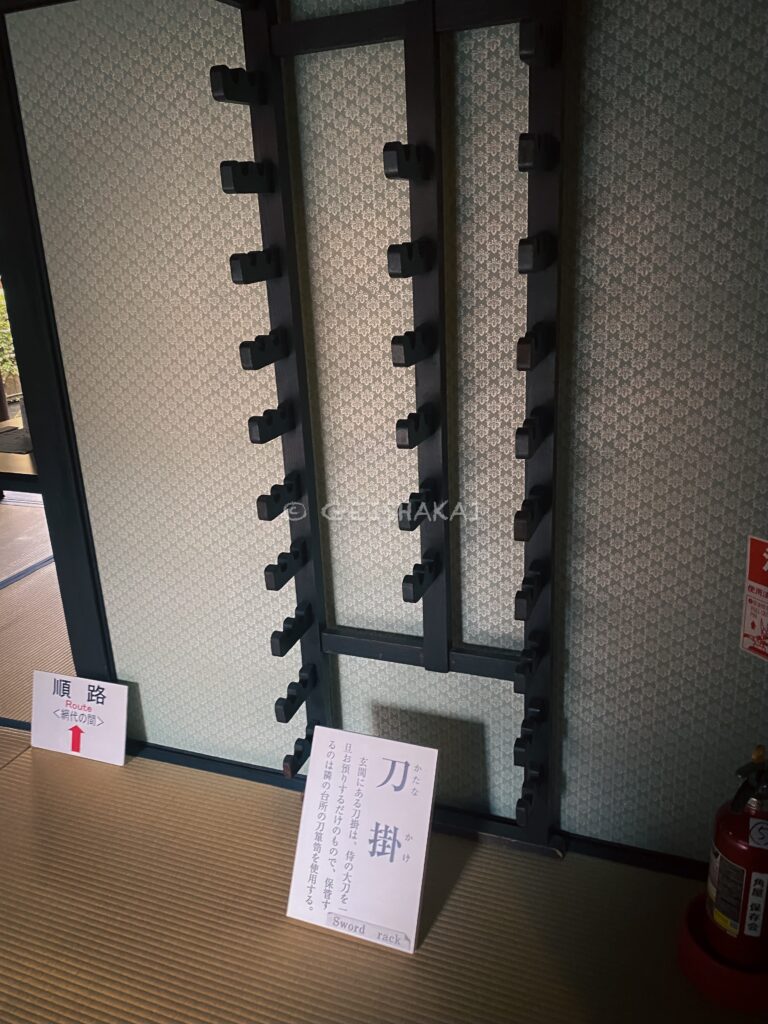

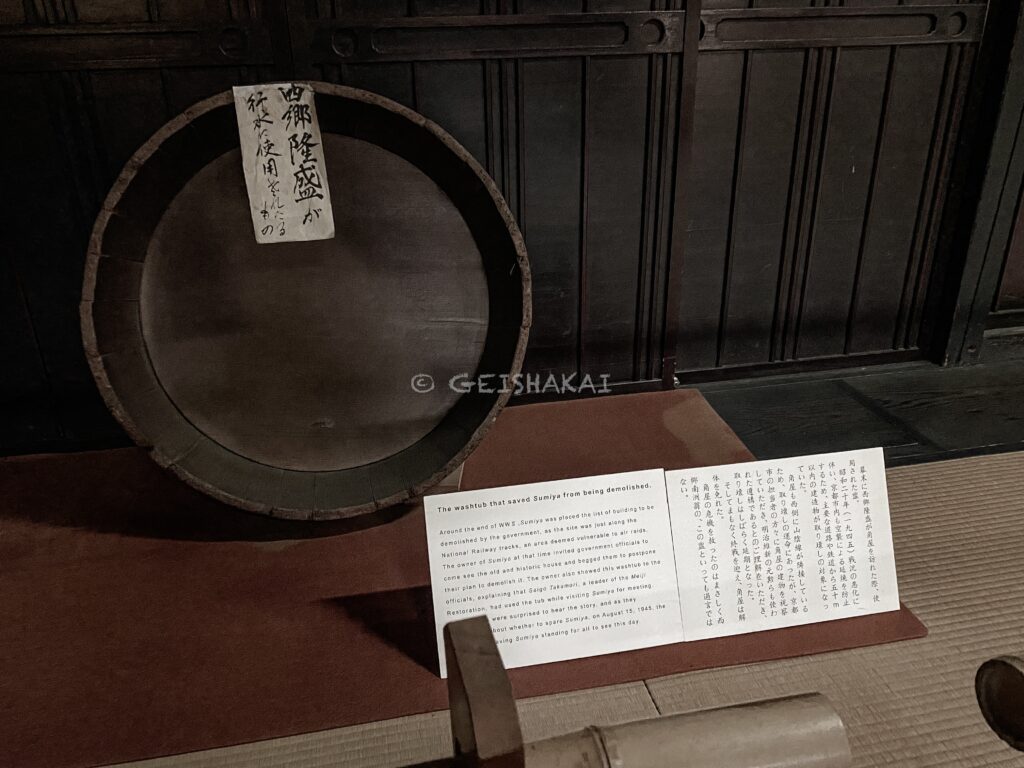

At the end of the Edo period, Sumiya became the meeting place for both the Imperialists and the supporters of the shogunate, thus it is considered to be a historic site of the Meiji Restoration. However, it has never been the scene of any brawl, except a minor incident with Shinsengumi’s katana blades in the hallway that left cut marks on one of the wooden pillars. All visitors were obliged to entrust their swords in a tansu chest at the entrance upon arrival as a strict “no weapon” policy has been enforced at Sumiya for centuries. Obviously, nowadays, it’s illegal to carry any kind of a blade in Japan, yet the tansu still stands half-open, reminding the adventurers of more brutal times in Japanese history.

Reservations are required for touring Sumiya. No photos are allowed on the upper floor where a stunning maki-e tapestry is located in the old banquet halls. Nevertheless, please enjoy the excellence of the ground floor rooms that I was able to photograph.

Zen dry garden (枯山水 karesansui) with cherry blossoms blooming. Sumiya is modeled after Buddhist temples.

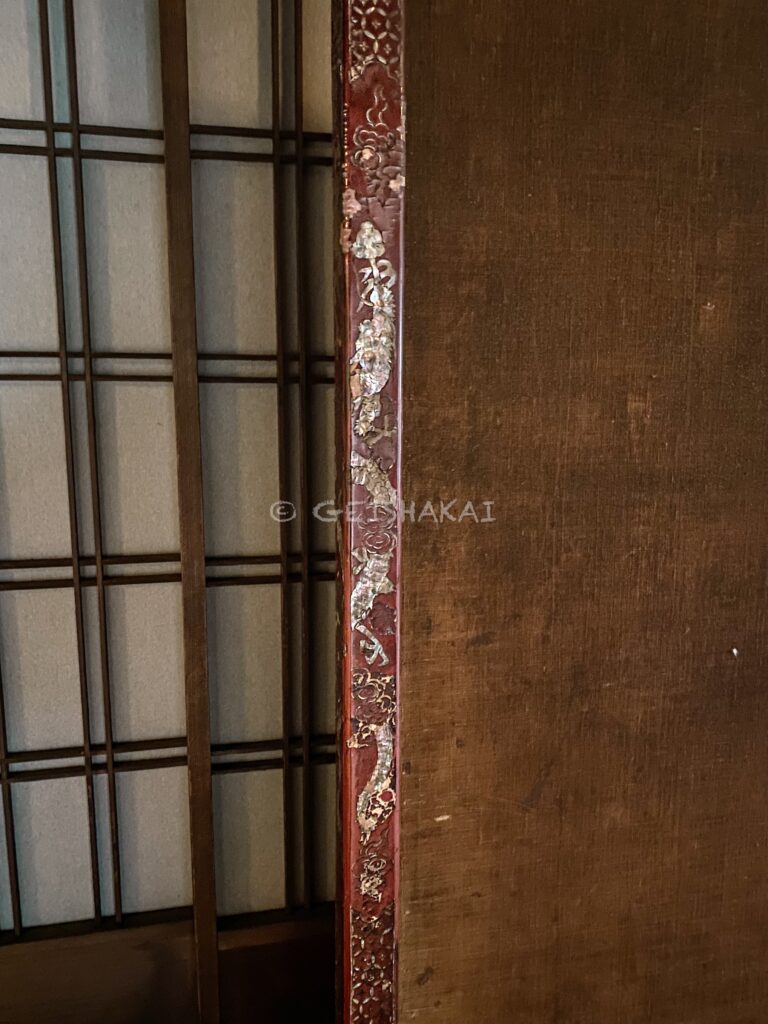

[above, first from the left] Beautiful room partition details—a dragon decoration made with a maki-e technique, using mother of pearl.

[above, in the middle] Yukimi windows allowed the guests to admire the winter snow falling in the garden.

[below, in the middle] Kitchen in the old machiya style. It is located on the ground floor and hidden from the guests who were led to the banquet rooms immediately upon arrival.

[below, on the right] Sumiya’s kitchen is unusually spacious for Kyoto’s entertainment districts. Ageya were equipped with a kitchen, while ochaya lack it and have the food delivered from the restaurants or temples.

Sumiya offers a window into a bygone era, where art, beauty, and strict tradition converged to create a melancholic tapestry of cultural expression. Shimabara was one of the most significant areas in Kyoto, the background for historical events. Immerse yourself in an authentic Edo period spirit next time you’re in Kyoto.

If you like this article, buy me a ramen or join me on Patreon! I don’t run any ads on my website so your support is the only way to keep it active ♡

Sumiya 角屋もてなしの文化美術館

One of my favorite examples of exquisite Edo period architecture. If the Sumiya’s walls had ears, just imagine what stories they could tell!